I Have Seen Hell, and it is White, 2009

The architecture of the first industrial revolution

I believe I have seen hell and it is white, it's snow white - were the words of the main character of Elisabeth Gaskell’s North and South novel, while encountering for the first time the harsh working condition of the workers in the cotton mills in Northern England, at the height of the industrial age. The social impact of the industrialisation was enormous. Freidrich Engels wrote in: The Condition of the Working Class in England, his account of the challenging aspects of England’s industrial transformation. His reports of mid-19th-century Manchester were uncompromising: a place of dirt, squalid over-crowding, and exploitation. His conclusion was, quite simply, ‘Hell upon Earth’.

Today, thankfully, our reality -at least in England- is very different.

Dalton Mills, a cotton mill complex built from 1866 to 1877 in Keighley – Northern England, is a Victorian textile mill, and one of the most important monument of its kind surviving today. Once the largest textile complex in the region, the mill was employing over 2000 workers. As the textile industry declined, the fortunes of Dalton Mills changed and in 1994 the operations were discontinued.

The interiors today are still breath-taking. Highly decorated iron pillars on every floor, with their intricate Victorian design, allowed the shafts to propagate motion across the production floor through belts, which were emitting a deafening noise (majority of workers was specialised in lip reading…). The worn staircase offers a reminder of how many people have worked here and a suggestion of their chatter while coming to work in the morning.

Walls and windows are muted, now that the building has lost its function, they seem spiritually relieved. Today they have nothing more to offer, other than an opportunity to reflect on the ways of working during the industrial revolution.

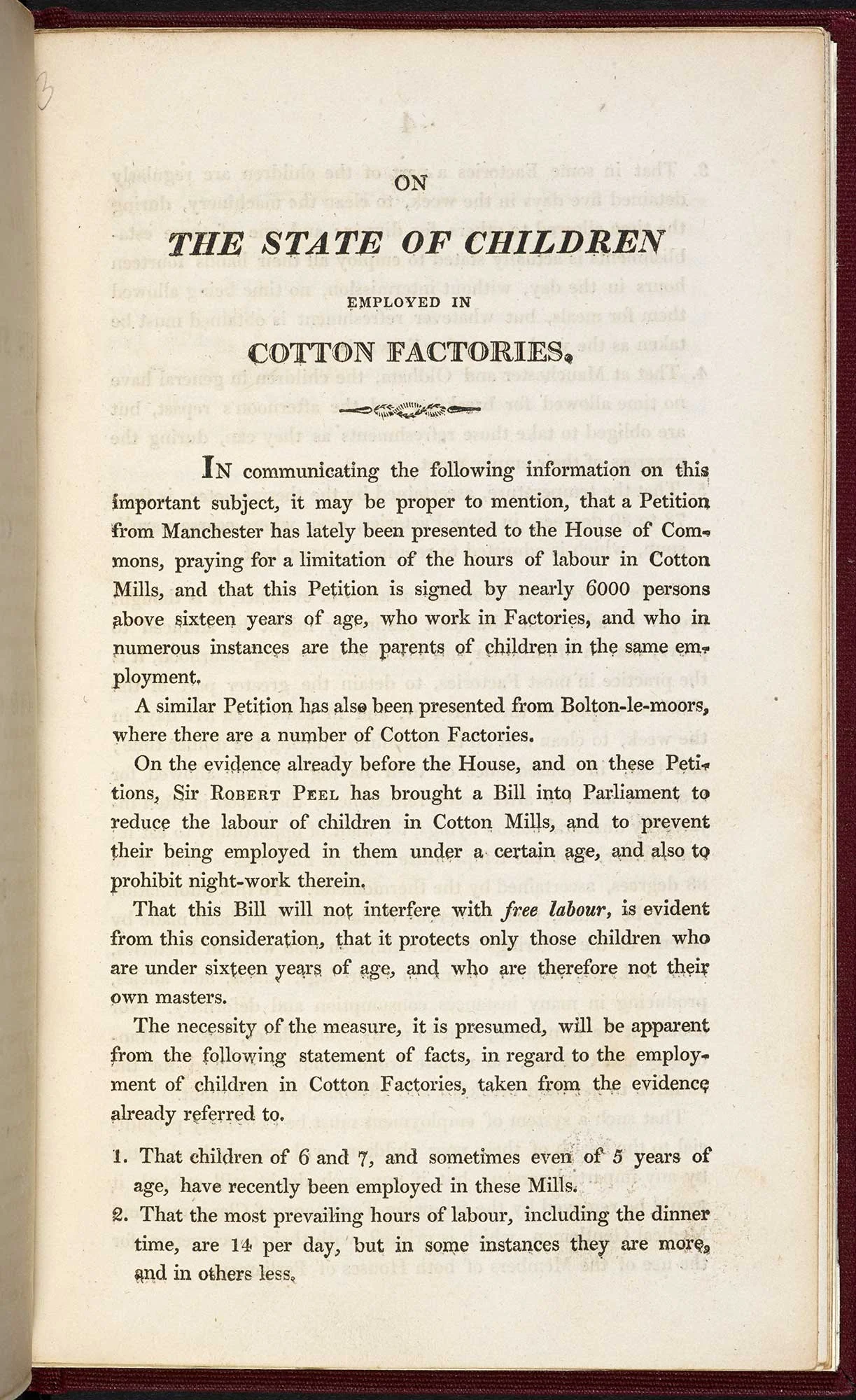

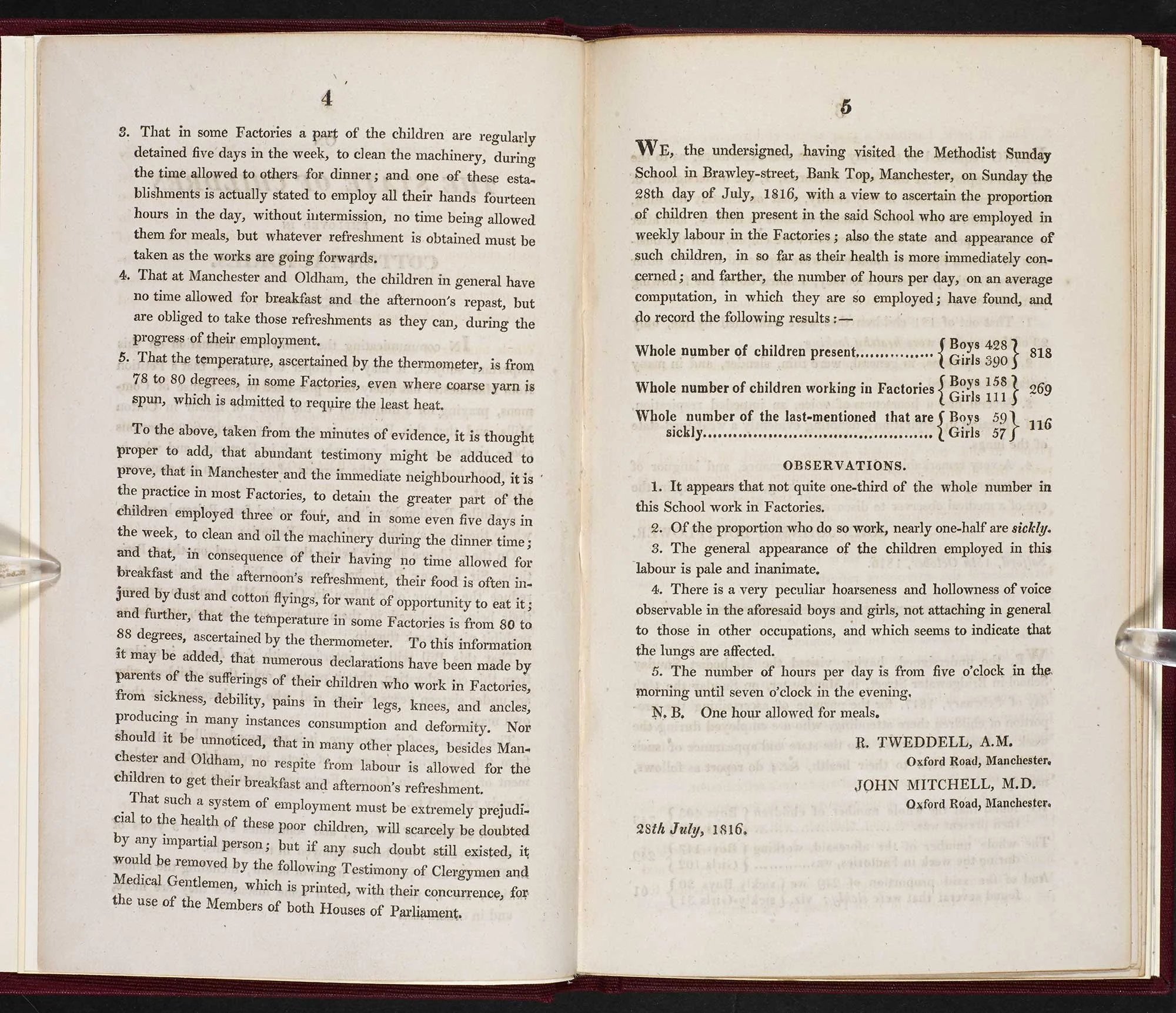

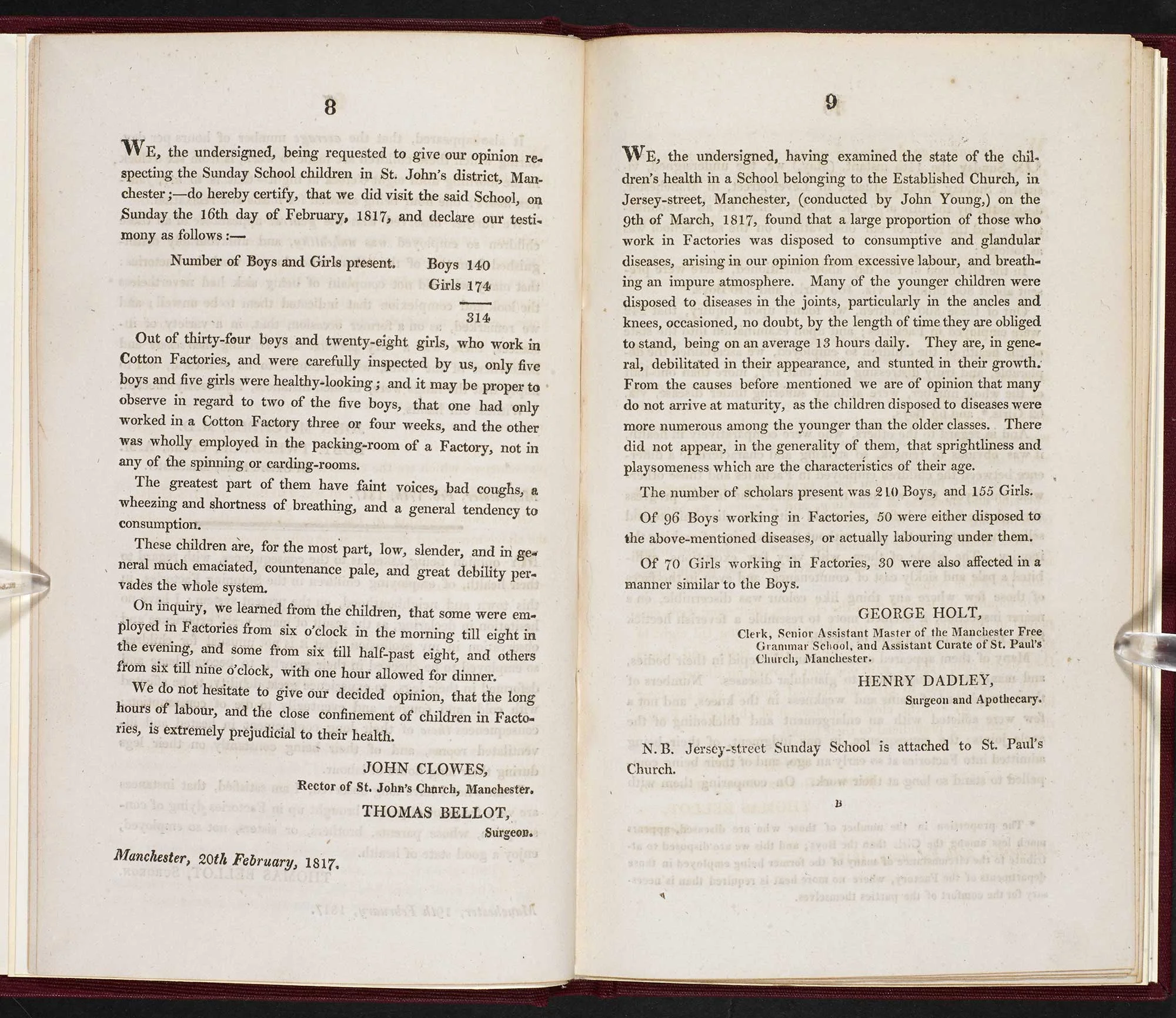

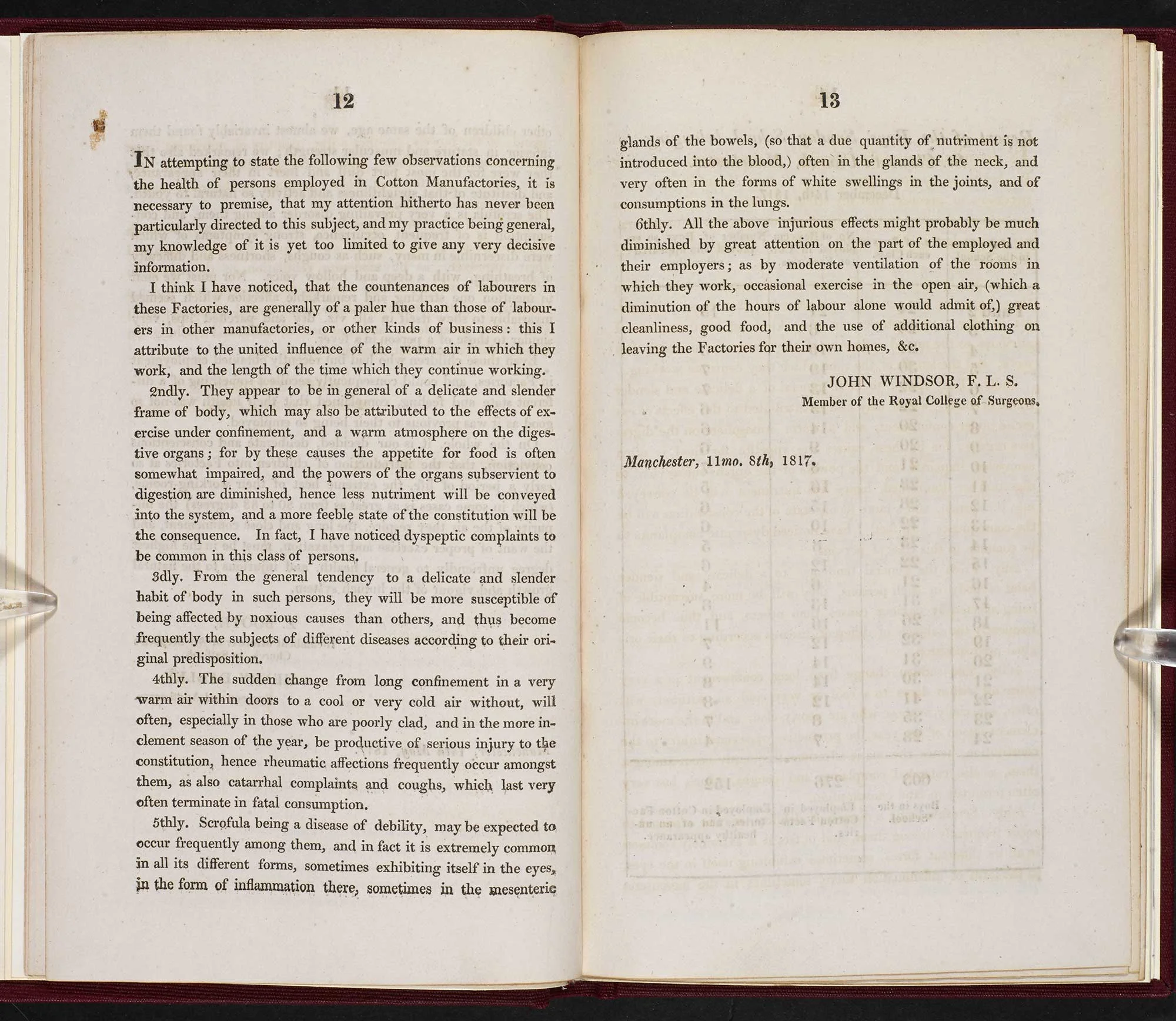

To learn more: On the state of children employed in cotton factories, 1818

Published in 1818, this book contains statistical information on the health of the vast numbers of children working in cotton factories around Manchester. Doctors and surgeons, often working with ministers and curates, visited Sunday Schools between 1816 and 1818 to conduct research. While assessing the health of the children, examining everything from colds and coughs to muscle strength or evidence of deformity, information was also collected on the children’s working hours and the amount of time allowed for meals. This evidence fed in to the 1819 Cotton Mill Factory Act, which although never properly enforced, was designed to prevent children under nine years old from working in cotton factories and to restrict the working days of children in other factories to 12 hours. Medical inspections were seen to provide substantial evidence that factory conditions had a detrimental impact on children’s health, although little statistical evidence exists to compare the health of employed and non-employed children. [source: British Library].

All rights reserved 2007-2018